It distresses me when people scoff at the Beach Boys!

I presume when it happens that the scoffer is in error, that they’re projecting the popular image of the Beach Boys – beachy, surfy, voicy – onto a richer version of their history.

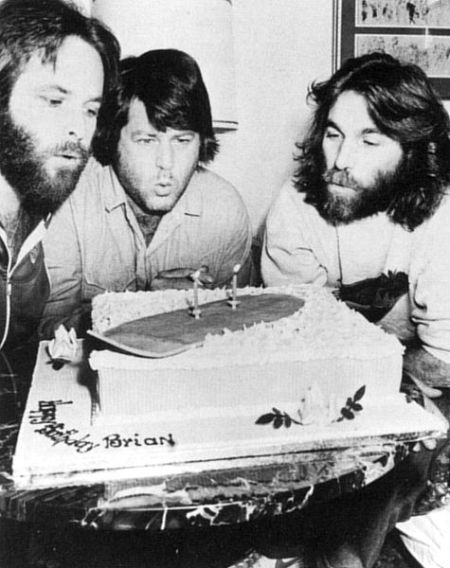

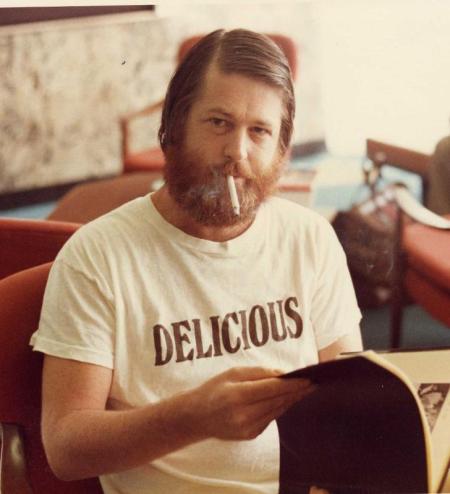

Maybe that’s wrong. Maybe it’s all a simper too far for some. But I can’t help but feel that the myth has overtaken reality. For the ‘Beach Boys’ is an acephalic entity missing one of its most important parts, that is, the rich vein of music that happened After the Fall, the 12 or 13 stone cold classic albums that come after the much-mythologised Brianian Collapse. These albums are concentrated in the 6 or 7 years after those post-Pet Sounds difficulties, but plenty of decent music carries on through the years, right up until the closing late-style suite on 2012’s That’s Why God Made the Radio. And maybe into Brian’s next solo album, where, who knows!, the duet with Zooey Deschanel might be great!

Anyhoo, this is the best music – for me – the best. I wouldn’t want to run a thread through all of it, through the rich imaginary of beaches and cars, the heart-dear ballads, the teenage – broken – symphonies, the mystic Weillian cantatas, the slowtime death-songs of the twilight period, the revenant but sometimes vital stuff of the postlapsarian 80s, 90s, 00s and 10s. But there’s a hardly fathoming stainlessness in the voice/s of this music that seems to me to be unique, or rare, in the history of music up until that point.

Of the many mechanisms of exclusion that structure musical and cultural history – class, gender, race, personality, happenstance – the fact that music before the recorded era needed at some level to be publicly voiced in one way or the other, that it needed to anchor functions or gatherings or whatever on the one hand, or that it needed to pass through technologies of power and representation to become a testimony of absolute music on the other, meant that the small moment, the diary entry, the miniature catastrophe or wonder, had to remain of personal note, lost to immediate exposure or to private joys.

But with recording, with the exposure and thickening of voices that are meek and weightless and the inscribing of forms that seem insubsutantial and transitory, you get something entering into the public record that feels new, or, again, rare. It exists beyond the ether of folksong and traditional music, where such ‘small’ feelings thrive, and also beyond the grand suffering of romantic classical musics that need a social stage to burn, despite their interior claims. Not all of the Beach Boy music works in this way – the big surf songs, for instance, are brashy in the public-facing way familiar to us – but some of the later examples (‘I Went to Sleep’ or ‘All I Wanna Do’, say) are so wispy that they almost fail to exist, and others (‘Surf’s Up’, ‘Til I Die’, ‘All This is That’) play with sonic or emotional frailty and tenderness in such a way as to expose something deeply unexpected. Others, like ‘This Whole World’ or ‘Dance, Dance, Dance’ are utterly joy-making.

So to a degree this music responds to and creates a new public, a new kind of listening, whilst also simply existing as great popular music. And found in much of it, public-facing or not, is a vulnerability that flickers like candlelight about to go out.

So why on earth are we here today?

In the interests of anyone who might potentially care, I’ve collected together my own personal canon of Beach Boys/Brian Wilson music. Personal bias, accident, inadequacy and so on all acknowledged. I’m in the castle of fandom here, firmly inside it!

This list is, hopefully, a shortcut to bliss. Every one of these tracks is in that category, you know the one, the imperishable, five-star, four-of-these-on-an-album-and-it’s-a-hall-of-famer category.

Any names in brackets denote not-Brian authorship. Other notes are at my whimsy. I’m not posting links cos the internet doesn’t pay me enough.

The Authoritative and Not At All Bullshit Stephen-Canon of Beach Boys and Brian Wilson Music

Surfin’ U.S.A – 1963

‘Farmer’s Daughter’

‘Lonely Sea’

Surfer Girl – 1963

‘Surfer Girl’

‘In My Room’

Shut Down Vol. 2 – 1964 (…holy shit we’re hotting up now)

‘Don’t Worry Baby’

‘The Warmth of the Sun’

All Summer Long – 1964

‘I Get Around’

‘All Summer Long’

‘Hushabye’ (Doc Pomus/Mort Shuman)

‘Girls on the Beach’

Beach Boys Today! – 1965

‘When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)’

‘Dance, Dance, Dance’

‘Please Let Me Wonder’

‘Kiss Me, Baby’

‘She Knows Me Too Well’

‘In the Back of My Mind’

Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) – 1965

‘Girl Don’t Tell Me’

‘California Girls’

‘Let Him Run Wild’

‘And Your Dreams Come True’

Bonus: ‘Guess I’m Dumb’, written for Glenn Campbell

Pet Sounds – 1966

‘Wouldn’t it Be Nice’

‘You Still Believe in Me’

‘Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder)’

‘I’m Waiting for the Day’

‘Let’s Go Away for Awhile’

‘Sloop John B’ (trad)

‘God Only Knows’

‘I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times’

‘Caroline, No’ (despite reservations about the lyrics)

Smile – the bootlegged version, the version released by Brian and his band in 2004, and the Smile Sessions from 2011.

Every single fucking second of these blessed albums, my favourite/s ever, beamed in from genius town. Many songs appear on subsequent albums in different forms, anyway, so I’ll include those by way of specificity.

Smiley Smile – 1967

‘Heroes and Villans’

‘Vegetables’

‘Little Pad’ (the only one here not originally from Smile)

‘Good Vibrations’ (!)

‘Wind Chimes’

‘Wonderful’

Bonus: ‘You’re Welcome’, ‘Their Hearts Were Full of Spring’, ‘Can’t Wait Too Long’

Wild Honey – 1967

‘Aren’t You Glad’

‘Country Air’

‘Here Comes the Night’

‘Mama Says’

Friends – 1968

‘Meant For You’

‘Friends’

‘Wake the World’

‘Be Here in the Mornin’

‘Anna Lee, the Healer’

‘Little Bird’ (Dennis’ first song!)

‘Diamond Head’

20/20 – 1969

‘I Went to Sleep’

‘Time to Get Alone’

‘Our Prayer’ (Smile)

‘Cabinessence’ (Smile)

Bonus: ‘Breakaway’, ‘Walk on By’ (Bacharach)

Sunflower – 1970

‘Slip on Through’ (Dennis)

‘This Whole World’

‘Deirdre’ (Bruce Johnston with Brian)

‘All I Wanna Do’

‘Our Sweet Love’

‘At My Window’

‘Cool Cool Water’ (Smile)

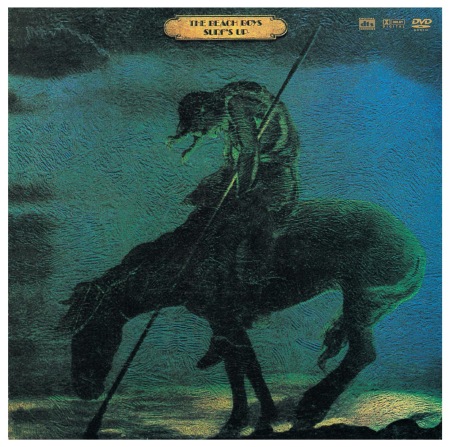

Surf’s Up – 1971

‘Disney Girls’ (Bruce)

‘Feel Flows’ (Carl)

‘A Day in the Life of a Tree’

‘Til I Die’

‘Surf’s Up’ (these two songs are everything, the second is from Smile and is my favourite song)

Carl and the Passions – “So Tough” – 1972

‘All This is That’ (Carl, Al and Mike, uses ‘Jai guru deva om’ in the lyrics, but is much better than ‘Across the Universe’)

‘Cuddle Up’ (Dennis, it’s always boggled my mind how this isn’t worshipped)

Holland – 1973

‘Steamboat’ (Dennis)

Bonus: The whole of ‘Mt. Vernon and Fairway (A Fairy Tale)’, a wonderful little curio of a drugged children’s story thing.

15 Big Ones – 1976

‘That Same Song’ (mainly for that priceless performance on YouTube)

‘Just Once in My Life’ (Carole King, Goffin and Spector)

Love You – 1977 (like Holland, this is an interesting album, but with only one standout)

‘The Night Was So Young’ (honorable mention to ‘Mona’)

M.I.U. – 1978, starting to get straggly here, but ‘My Diane’ and ‘She’s Got Rhythm’ are worthwhile, if not canon-standard!

LA (Light Album) – 1979, ropy too, but ‘Good Timin’ benefits from the unmatchable Brian and Carl combo, and Bruce’s disco-fication of ‘Here Comes the Night’ is always worth a laugh.

‘Baby Blue’ (Dennis – Breaking Bad missed a trick using the Badfinger song instead of this glorious thing in the final episode)

That’s Why God Made the Radio – 2012

‘From There to Back Again – Pacific Coast Highway – Summer’s Gone’ (the closing suite on what’s likely to be the last BB album, great they got such a strong and apt send-off)

BRIAN SOLO

Brian Wilson – 1988

‘Love and Mercy’

‘Melt Away’

‘Rio Grande’

All of Orange Crate Art (1995) is worth checking out, not least for VDP’s wackedness.

Imagination – 1998

‘Your Imagination’

‘She Says That She Needs Me’

‘Lay Down Burden’

Gettin’ in Over My Head – 2004

‘Saturday Morning in the City’

That Lucky Old Sun – 2008

‘Can’t Wait Too Long’ (Smile)

‘Southern California’

That’s it! I would argue you’re mean if you don’t enjoy the music above.

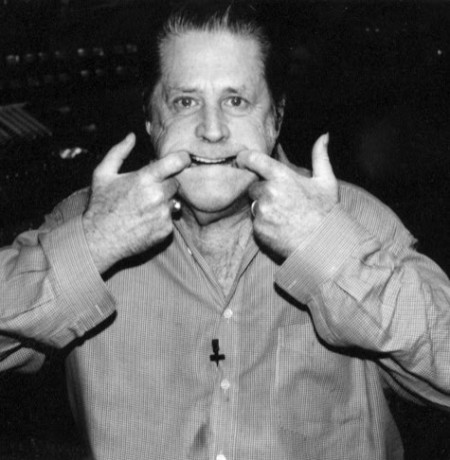

Before I go, okay, maybe one clip: